The Soul of the Boijmans

Text by Rab Messina

Photography by Lotte Stekelenburg

Dutch filmmaker Sophie Dros followed the owner of nearly a dozen life-like sex dolls in the UK. Middle-aged and perennially single, suffering from an unresolved Oedipal complex, viewers of the half-hour examination can find out more about him from the way he wants his doll to treat him than from the often heart-breaking soundbites coming from the horse’s mouth. That is, it’s not just that he sees a soul in those plastic creations –it’s more a case of his own soul being contained in them.

My Silicone Love, a documentary, is one of the pieces selected by guest curator Hans van der Ham for Anima Mundi, a new exhibition at the Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen in Rotterdam. As the title literally means “world soul,” van der Ham set out to explore the emotional links

between man and inanimate matter and our age-old desire to breathe life into objects.

We spoke with the Rotterdam-based artist about his selection, the role of artificial beauty and how anthropomorphism messes with our creepiness detectors.

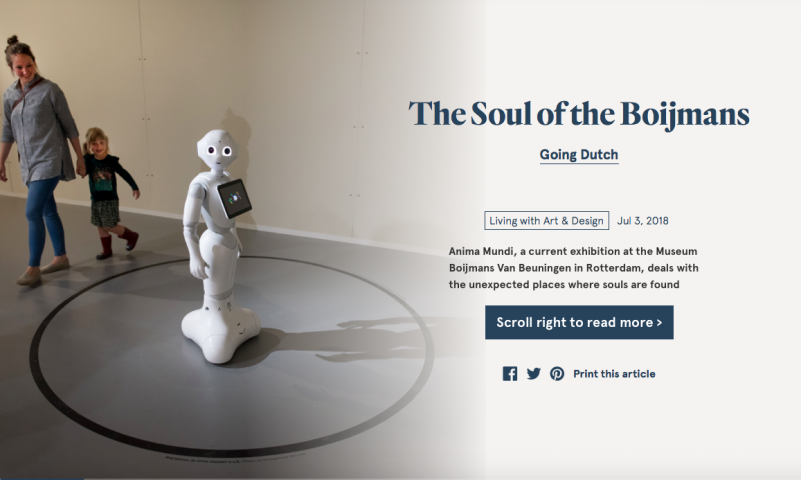

TLmag: After seeing the teddy bear, I went back to Pepper, the host robot: I found it unnerving that something that should inspire trust and comfort –the plush bear– did the contrary, while something that should inspire mistrust and discomfort –the robot– got away with the opposite. Was that part of your goal?

Hans van der Ham: This is exactly what it is about! We live in an era where robots and

artificial intelligence are coming up; this will have great impact on humans, especially on the emotional [side].

But, and this is my goal for the exhibition, this is not really new in life. Ever since the ancient Greeks –and I think even far before, since the beginning of mankind–, people have had emotional relations with matter. It seems that man wants to allow life to matter. That’s why in her book Art, Agency and Living, professor Caroline van Eck talks about our species as being the Homo Animans.

It is a fact that before 1800 people looked at a work of art in a different way, compared to the way we do nowadays. We cannot imagine this anymore, but the involvement with an art piece was

like having a relationship with a real person.

In Anima Mundi I wanted to show this emotional bond of humans with matter through history –and art history– and different cultures.

The script written for the cute little robot speaks of attractiveness. How is something so tangible still part of the intangibility of a soul?

It depends on what we want to see in it. It’s a kind of projection, like children do with their teddy bears or dolls. In Japan, they believe that everything has a soul. This resembles the anima mundi belief of the ancient Greek. If in Japan a robot “dies,” the soul has to be taken out –mostly by a priest in a temple.

How does the Inez and Vinoodh photo connect to the rest of the pieces?

Those works were made in the beginning of the Photoshop era. This means that what you see is not what you see. It’s artificial, much in the same way robots are artificial nowadays.

Why did you decide to include the slices of life in the shape of foetal and head cuts? Which objects in the exhibition are they most closely parallel to?

I wanted to show life and death as the only two realities. With the artificial reality of robots and AI, we are trying to escape this. It’s the same thing alchemists did historically: they were searching for the philosopher’s stone and the elixir of life in an attempt to get reach eternal life by transforming matter.

How did you come upon Sophie Dros’ short film?

I stayed there for the full 27 minutes. It did more to drive the point of emotional transfer than the likes of Spike Jonze’s Her.

I think that’s because it’s a real documentary instead of a fictional movie. This man is really having a relationship with the dolls, because he has not been able to have a serious relationship with a real, flesh-and-blood person.

What does the dark facial covering represent in Michaël Borremans’ The Angel painting? Why did you decide to feature it?

That painting is a beautiful mystery; it leaves you with only questions. “Angel” refers to the afterlife, but it isa real person standing there. But, is it a man or a woman? What is her/his real face hiding behind the mask? We will never know, and it brings us back

to our own imagination. In this way, the person standing there could be either you or me or everyone.

Anima Mundi is on display until September 23