ANIMA MUNDI

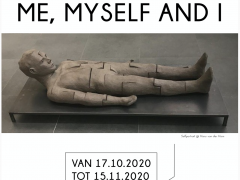

It is easy to become emotionally involved with an artificially created likeness. That has always been true. There are people who have fallen in love with the noble features of a Greek marble statue while others have embraced the muscular back on a drawing by Michelangelo. Who has not shared the sorrow of the painted mother bearing her dead child in her arms? Works of art may be true to life, but they are never flesh and blood. Yet they can still inspire us as much as the truth.

Inspiration is also a central theme in areas other than visual arts. Religions based on the worship of nature suggest that everything is pervaded with good and evil spirits, which can be appeased in rituals with specially designed costumes and attributes. In ethnographic thinking, the worlds of the spirits and the living coincide. Alchemy, the predecessor of modern chemistry, is also based on the assumption that everything is connected. Living and dead material are both derived from the same basic ingredient; the alchemist searches for the elixir of life, which brings immortality. Another early science in which inspiration plays a role is anatomy. By carefully studying the human body and by analysing how the different parts connect with each other, such study has scouted the area between the body as a machine and man as a living (and innovative) organism.

The Anima Mundi exhibition has been organised by the Rotterdam-based artist and guest curator Hans van der Ham. He brings together works of art and artefacts from the historic areas stated with examples from contemporary art and science. Van der Ham sees the current spectacular developments in biotechnology from the perspective of the tenets of alchemy. Viable organ tissue has now been created in a laboratory. He recognises in the detailed anatomical studies from the renaissance a foreshadowing of robotics as we know them today. With the aid of contemporary art, he shows that in our time, after a period in which art was abstract and intercourse with the material held a central position, the emotional interaction between spectator and work of art is being strengthened. “Figuration has gained the upper hand and the narrative aspect has again assumed an important role. Art may once again be deeply emotional”, says Van der Ham.

An extra layer is formed by the (films about) robots, which will be shown in the exhibition. The increasingly emotional connection signalled between man and (art) objects can also be seen within robotics. It would appear that we humans are developing a certain emotional relationship with robots. There are examples of robots being deployed (primarily) for combating loneliness. The question is, however, whether robots are going to become more like people or people more like machines, programmed by a society in which the advance of technology has only just started.

Anima Mundi takes a small journey through art history - with diversions to ethnography, alchemy, anatomy, biotechnology and robots - in an attempt to show which aspects play a role in creating an emotional connection between people and works of art.